'31 Nights of Horror' Day 13: House of Hunger, Book Review

Blood, Power, and Seduction: A Gothic Symphony of Horror

Hi Besties,

Sorry for the lack of content recently. I went through a major hurricane in Florida, and during that time, I wasn’t able to watch any movies or do much of anything due to the loss of power and internet. However, during this downtime, I actually read a book! So today’s newsletter is a little different as I get back to the 31 Nights of Horror. I read House of Horrors in just two days, and it was an absolute blast. Below is my review—hope you enjoy it!

Hey, ghouls! 31 Nights of Horror is here, serving up daily scares with reviews of classic and new horror films. Watch for chilling lists and other spine-tingling pieces. Keep your lights on… the terror begins now

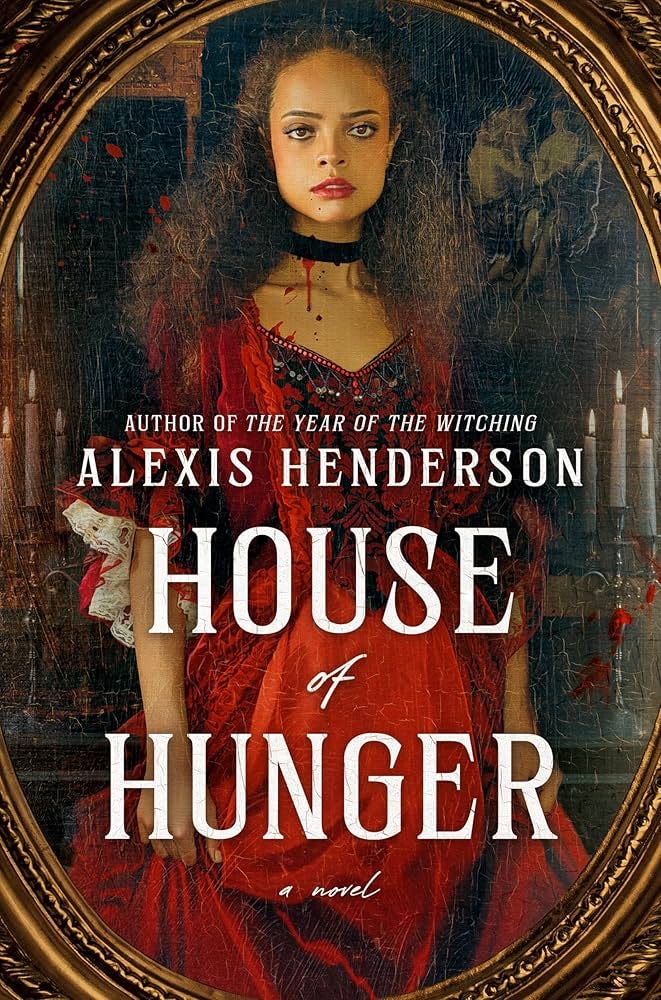

House of Hunger by Alexis Henderson is the kind of novel that sinks its teeth into you, slowly, almost seductively, before you even realize the danger you're in. It’s a dark, gothic symphony that plays with the familiar notes of vampire lore but transforms them into something far more sinister, and far more beautiful. This is a story that lures you in with promises of grandeur and glittering wealth, only to reveal a darkness so deep, so consuming, that by the time you see it for what it is, it’s too late. You’re already under its spell.

Marion is the perfect protagonist for this tale of temptation and ruin—a young woman from the South, worn down by poverty and desperation, her spirit slowly being eroded by the cruelty of the world she knows. The South is a bleak place, filled with soot and smoke, with no future for someone like her, trapped in a life of labor that grinds her down day by day. So when she hears the whispers of a better life in the North—a life of opulence and ease, all in exchange for something as simple as her blood—how could she resist? Marion’s desperation is palpable, and Henderson writes her with such empathy, allowing us to feel the weight of her choices, the pull of escape that leads her into the arms of the Northern aristocracy.

The world of the North is a study in contrasts—beautiful, cold, and deadly. Henderson builds it with such lush, vivid detail that you can almost feel the chill in the air, taste the rich, decadent meals, and see the velvet shadows that cling to every corner. The nobles of the North live in grand, sprawling estates, their lives a haze of luxury and privilege. But there’s an eerie stillness to it all, a sense of something rotting beneath the surface. The House of Hunger, where Marion is taken to serve as a bloodmaid, is a place of both splendor and horror. It is a gilded cage, a palace of wonders and nightmares, where the walls are soaked in secrets and the air is thick with dread.

And Lisavet Bathory—what a character. She is both everything you expect and nothing you can predict. A woman of great power, whose beauty is the kind that blinds you to the menace beneath. She’s no ordinary vampire—not that Henderson ever directly calls her that—but something far more alluring, far more dangerous. Lisavet doesn’t just take blood; she takes control, in the most intoxicating way. Her charm is lethal, her presence magnetic, and as Marion falls deeper under her spell, you can feel the danger tightening like a noose. Lisavet is both predator and savior, a figure who straddles the line between the divine and the monstrous. She embodies the very heart of the story’s seductive menace—the idea that power corrupts, that desire blinds, and that sometimes, we willingly walk into the jaws of the beast.

What Henderson does so brilliantly in House of Hunger is play with the idea of consumption—not just the physical act of drinking blood, but the way the upper class devours the lower. The bloodmaids, with their delicate, pampered lives, are given every luxury imaginable, but at what cost? They are taken from their homes, their lives, and used—drained—until there is nothing left. The aristocrats of the North live off their suffering, their desperation, their very life force. It’s a sharp, searing commentary on class and privilege, one that feels all too familiar in a world where the rich feast on the labor and pain of the poor. Henderson’s writing is laced with this kind of biting social critique, but it never feels heavy-handed. Instead, it creeps up on you, like the slow, insidious rot beneath the beauty of the House of Hunger.

Marion’s journey is one of gradual, creeping horror. She starts as a girl in search of escape, seduced by the beauty and allure of the North, by the promise of a better life. But as she ascends into the world of the bloodmaids, she begins to see the cracks in the façade, the darkness that lurks beneath the glamour. It’s a slow burn, a gradual awakening to the horror of her situation, and by the time she realizes the truth, she is already entangled in it, unable to break free. Henderson’s pacing is masterful here, drawing out the tension with exquisite precision, making you feel the slow, tightening grip of the story’s dark heart.

The horror in House of Hunger is not just in the blood and the violence, though there is plenty of that—it is in the atmosphere, in the sense of doom that permeates every page. The House itself feels alive, a living, breathing thing that feeds on its inhabitants. The way Henderson describes it—the dark halls, the flickering candlelight, the heavy velvet drapes—it’s all so richly textured, so vivid, that you feel like you’re there, walking those cold corridors, feeling the eyes of the house on your back. And the blood—it’s everywhere. It’s ritualized, almost worshiped, a currency of power and control. The act of taking blood becomes something sacred, something that binds the bloodmaids to their mistresses in ways that go far beyond the physical.

But what really makes House of Hunger stand out is the way it subverts the typical vampire narrative. Henderson gives us all the elements we expect—the blood, the seduction, the aristocratic excess—but she twists them, reframes them, until we’re left with something wholly original. These are not just vampires—they are symbols of a system that consumes the weak, the desperate, the poor. And Marion, for all her flaws, is the perfect lens through which to explore this world. She is complicit, yes—she sees the horrors and chooses to look away, to justify them, because she wants so desperately to belong. But she is also a victim, trapped in a system that uses her, that bleeds her dry.

House of Hunger is a dark, seductive, and ultimately terrifying novel. It is a story of power and privilege, of desire and destruction, of the ways in which we are all complicit in the horrors of the world we inhabit. Alexis Henderson is a master of gothic horror, and this novel is a shining example of her ability to take familiar tropes and twist them into something new, something chilling, something unforgettable.